- EverythingAutism.org is a parent-driven resource guide for parents of kids, teens and adults with autism in the Clear Lake area of Houston. We welcome your submissions! Have a provider or resource you want to share with other parents, feel free!

Budget Rider 70 & Public Accountability for SPED

Previously I commented on the difficulty of obtaining good information about schools, both in terms of available services and student outcomes, to help parents of autistic kids determine where their child might have the best opportunities. Budget Rider 70 (Texas Senate Bill 1, Rider 70, III-19), whose provisions may be found here, may have taken a small step toward establishing a publicly accessible uniform accountability rating system for special education.

Each time I moved to Houston—we’ve done two round trips to California and back in the last 12 years—I attempted to do my due diligence on school districts long distance, only to have the decision of what part of town we move to come down to anecdotal information gleaned from a collection of dated blog posts on City-Data.com, like this one:

. . . along with communication from parents I didn’t know complaining of having to do battle with their school to get what they described as needed services for their child (at which point, you have to judge if the parent is reasonable or not); and brief conversations with busy school administrators who don’t want to talk to you, since your child doesn’t go to their school, or they can’t say how their school compares to another anyway because they really don’t know.

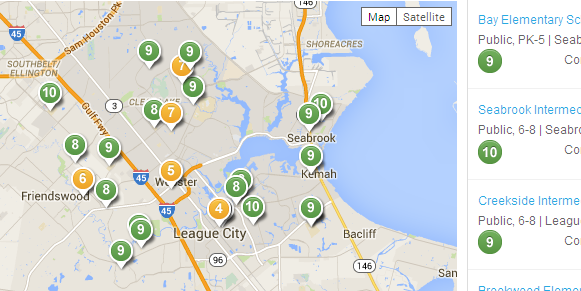

GreatSchools.org, SchoolDigger.com and other sites provide information about which schools are best for typical kids—we decided the school had to be “at least an 8” for our other son—but we had no idea how that 8, 9, or 10 school would be for our intellectually disabled child. In fact, we worried that at a more competitive school, a special needs kid would be more likely to be isolated.

Parents of typical kids have GreatSchools.org rating scale, shown above. Nothing like this exists for Special Ed programs to allow parents to compare schools.

I contacted the Texas Education Agency expecting to be directed to authoritative information about best schools in the greater Houston area for a kid with autism.

For those unfamiliar with the TEA, that is the agency charged with rating public and charter schools in Texas. They are the ones who decide if a school is “exemplary” or “recognized,” based largely on standardized test scores. When I called the TEA and was transferred to Special Ed, instead of the objective information I was seeking, I got the opinion of the person I was conversing with, someone living in Austin (where the TEA is located), who’d just happened to have had “boots on the ground” (as she put it) in Katy. She thought it was pretty good. She knew nothing about Clear Lake or any other district in the Greater Houston area, however.

That’s when I discovered that the TEA didn’t track special ed students in a way that permits meaningful comparisons between schools. This is not to say that the TEA does not actively monitor and gather data on special education students—they (and other agencies) do; so much so that the paperwork is burdensome for SPED teachers, who want to spend time teaching students and not filling out paperwork.

I contacted the TEA again in 2014 about any available data to compare school and school districts, I got the response in an unsigned email that they “do not believe assessment for special ed programs is possible, since education is individualized for each child.”

Then, upon learning about a SPEARS (Special Education Ad Hoc Reporting System) database at the TEA, which supposedly containing information about Special Ed outcomes, classroom placement, and so forth, I contacted the agency a third time and requested stats on my school district—though I was warned by the “PBMAS“ Database Administrator, who was charged with performing my information request, that I would not be able to understand the report that the system generated and that it was not really going to address my needs. He was right.

What you get at the end of end of it are tables full of meaningless numbers without context–like getting lab work back and not knowing what’s normal or what one should be worried about. Just as the TEA staff person predicted, the results of my information request were totally useless.

Bottom line is that the public agency charged with a public accountability rating system for public and charter schools in Texas has never been required to establish a public accountability rating system for special education programs which would allow parents to evaluate and meaningfully compare schools–or even to permit outsiders to make use of the data to learn what other schools are doing right.

But things may be starting to change in terms of public access to information about schools.

Budget Rider 70 is an initiative whose original purpose was to establish a unified reporting system for special education throughout Texas in order to lessen the administrative burden on teachers, who now have to be accountable to multiple, often duplicating SPED reporting systems.

However, during the public comment period, it became clear that making this information available to the public in an easily understood format was a priority for many stakeholders, even if this was not the original intent of the bill.

In the statement submitted by the The Arc of Texas, Disability Rights Texas and The Texas Council for Developmental Disabilities, it became clear that at the end of the day, public reporting and accountability for special education programs was what was most desired by parents and groups:

“Parents of students with disabilities receiving special education services . . . other stakeholders need better access to data about special education services in their district so they can provide appropriate input to TEA and to their local school district.

Most parents [of students with disabilities] are not aware of monitoring and accountability practices including how to locate and understand the school’s monitoring and accountability ratings and how to provide input to their school or TEA regarding their satisfaction with services (outside of the formal dispute resolution processes).

Currently data that are available about the school’s performance on specific measures related to special education services from PBMAS and the APR are not easily accessible, understood, or used effectively to support improvements in services to students with disabilities, or to make changes to policy and practice at the local district and campus level.

Parents and other stakeholders need access to information presented in a usable way. Plain language summaries of a district or campus’s achievements and progress would be invaluable.

Much of the data available currently [from TEA’s PBMAS] is presented in table format, with little context. It is jargon-heavy and relies on acronyms outside the average person’s lexicon. The measures used are not familiar to most people. A parent or other stakeholder attempting to make sense of the data without the assistance of someone very familiar with the educational system in Texas would be left floundering.

Thank you, Arc of Texas, for representing the needs of parents so accurately and eloquently!

The Arc of Texas emphasized that Budget Rider 70 should create not just a unified reporting system for special education, but one that would provide clear information to the public.

However, the recommendations that were specifically adopted by the Bill were as follows:

- Ensure duplicative documents and reporting are not requested [of teachers and school administrators].

- Set up structures such that a given document can serve several purposes.

- Provide templates for as many documentation requirements as possible.

- Combine a performance-based system with random, on-site visits to schools.

- Gather input from teachers, other staff, and parents regarding the quality of the school’s overall special education program.

- Combine, link, align, and/or eliminate indicators where possible to ensure a single, unified system for monitoring special education.

- Combine the three separate special education systems—State Performance Plan (SPP), the Performance-Based Monitoring Analysis System (PBMAS), and the residential facilities (RF) monitoring and RF Tracker system—into a single, integrated, non-duplicative monitoring system with a single reporting schedule such that an area is only addressed once.

- Consult regularly with a variety of stakeholders regarding the ongoing implementation of accountability, monitoring, and compliance systems related to special education.

- Ensure that changes made to the accountability, monitoring, and compliance systems related to special education are consistent with the goal of ensuring that every student has access to a free appropriate public education.

- Increase transparency and make results easily accessible for stakeholders by providing a standard template to communicate results of performance and compliance indicators.

- Provide technical assistance to school districts struggling to appropriately provide services to students with disabilities, and, when necessary, intervene and enforce sanctions when districts are unable or unwilling to correct noncompliance and violations of the state and federal laws.

- Continue and improve the monitoring of districts that serve students with disabilities who reside in RFs [Residential Facilities].

- Include indicators focusing on passing standards for state assessments in an area that affects a district performance indicator and not just that of “special education.”

I’m not sure whether #10 the recommendations of Budget Rider 70 constitutes a mandate to the TEA to think about how to present the data the agency is collecting to the public in a way that is accurate, meaningful, and easily understood by parents, but it is perhaps a step in the right direction.

Emily Nedell Tuck